WHEN WALLS SPEAK:

Reading Melbourne Through Its Posters

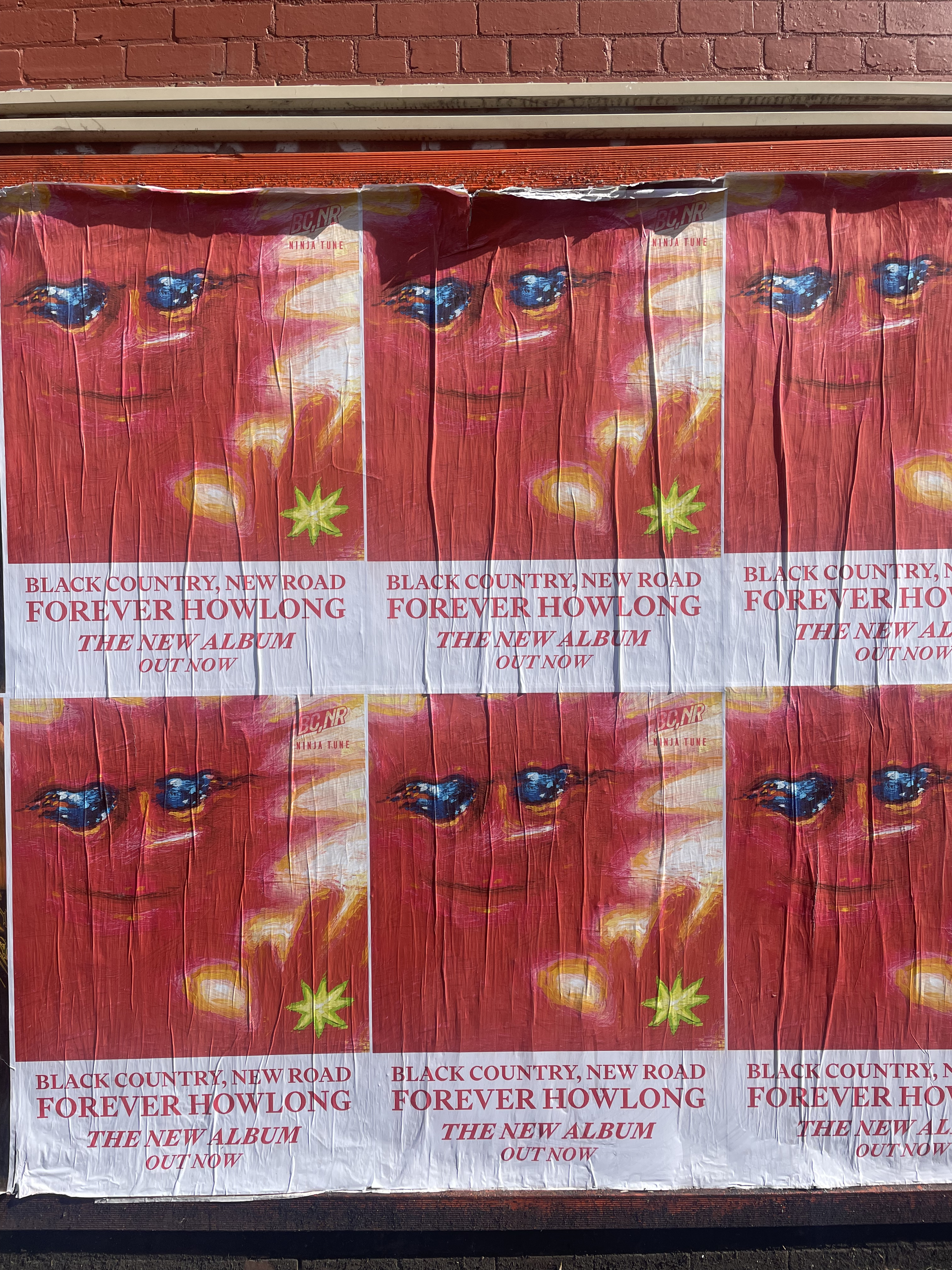

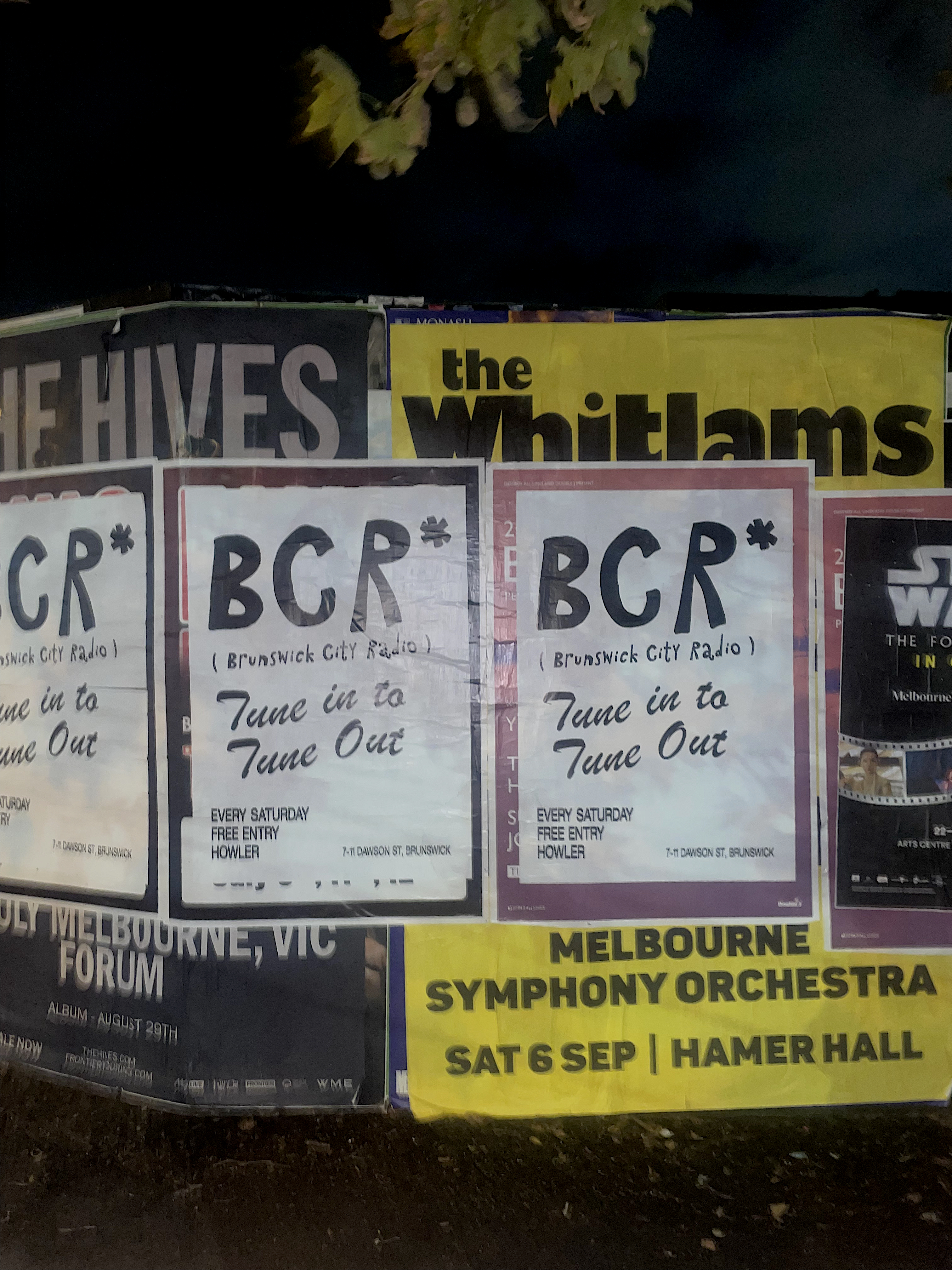

Every time I walk through Melbourne, I keep stopping. Not because of traffic, my phone, or an urgent destination, but because of the walls. Layers of posters — some freshly pasted, others sun-bleached and half torn — announce events I do not yet know, bands I have never heard of, exhibitions already passed and protests still to come. The neighbourhoods of the inner city constantly suggest possibilities. More than once, those suggestions have turned into action. I have attended markets, visited exhibitions and discovered music simply because a poster caught my attention.

Having lived most of my life in the Netherlands, this relationship with the street still feels unfamiliar — and increasingly meaningful.

︎︎︎Layers of posters intertwine with graffiti, forming a shared visual language across Melbourne’s streets. What might appear chaotic reveals a vibrant and constantly evolving urban canvas.

︎︎︎Layers of posters intertwine with graffiti, forming a shared visual language across Melbourne’s streets. What might appear chaotic reveals a vibrant and constantly evolving urban canvas.A Different Relationship With Public Space

In many Dutch cities, flyposting — known locally as wildplakken — once played a more visible role in public communication. Throughout the late twentieth century, posters were deeply embedded in political activism, cultural programming and subcultural movements. The Dutch design collective Wild Plakken, founded in 1977, even built its identity around illegal poster pasting, using graphic design as an instrument for social and political engagement.1

Over time, however, postering in the Netherlands became increasingly regulated through municipal visual management policies. Today, posters are typically confined to designated columns or official noticeboards, often limited in number and primarily reserved for non-commercial expressions of opinion.2 Municipal advertising policies frequently justify these restrictions by arguing that excessive or visually diverse advertising risks reducing the perceived quality of public space.3,4 The result is a communication system that is organised, monitored and temporary by design. Posters still exist, but largely as regulated information carriers rather than layered cultural surfaces.

Melbourne operates differently.

Here, posters spill across walls, hoardings, poles and laneways. While flyposting is technically illegal under local regulations, Melbourne simultaneously cultivates an international reputation built on street art and public visual culture. The city’s management policies attempt to balance removal and prevention strategies with recognition of street art and visuals as distinctive cultural assets.5

The result is not a fully permissive environment, but a negotiated one. Rather than eliminating visual density, Melbourne appears to coexist with it — a coexistence between enforcement and everyday practice. This density does not feel disruptive. It feels communicative.

The City as a Public Noticeboard

What stands out most in Melbourne is the breadth of what posters represent. They promote blockbuster exhibitions, major festivals and institutional programming, but they also advertise underground music nights, community gatherings, activist campaigns and small independent initiatives.

Posters here are rarely removed as soon as they age. New layers are pasted over older ones, producing surfaces that read almost like archaeological timelines of cultural activity. The walls do not simply display information; they record it.

In this sense, Melbourne functions as a giant, decentralised noticeboard — imperfect, shared and constantly rewritten by the people who live and create within it. These layered walls do more than circulate information; they reveal how visual communication shapes who gets seen, heard and remembered in the city.

Posters and Visual Power

Images in public space rarely exist neutrally. Urban scholars increasingly describe cities as environments governed through visual systems. Branding campaigns, graffiti removal programs, mural commissions and heritage preservation strategies all shape how cities are visually interpreted and culturally understood.6

At the same time, individual acts such as flyposting, stickering, placing political placards in street-facing windows or writing graffiti contribute to a collective visual discourse. While their creators’ values may differ, their ambition often overlaps: to claim a stake in shaping the image and cultural meaning of the city.

In this context, poster culture does more than advertise events. It contributes to an ongoing negotiation over identity, visibility and belonging in public space. Posters may promote music nights or exhibitions, but they simultaneously assert that cultural life is not solely curated by institutions or corporate branding strategies. Instead, it emerges through ongoing, collective participation in shaping the urban image.

Grassroots Culture

Melbourne’s density of printed material reflects the city’s strong grassroots cultural infrastructure. Grassroots culture7 emerges from the bottom up — initiated, produced and circulated by individuals, collectives and local communities rather than solely by institutions or corporate marketing structures.

Posters remain one of the most accessible tools for these initiatives. They are affordable to produce, easy to distribute, inherently local and physically tangible. Unlike digital promotion, they do not rely on algorithmic visibility, audience tracking or advertising budgets. Instead, they allow ideas to enter shared public space without requiring mediation by digital gatekeeping systems. They simply require an idea, a design and the willingness to occupy space.

Melbourne’s internationally recognised live music and arts scenes have historically relied on this visibility. The city’s dense network of independent venues, collectives and temporary events continues to operate through a hybrid communication infrastructure in which posters remain central.

In a city where graffiti and street art are deeply embedded in the visual identity — and actively promoted through cultural tourism strategies — posters feel less like intrusion and more like continuation. They participate in an established language of public expression.

Outside the Algorithm

Unlike digital advertising, posters are not personalised. Everyone encounters the same message regardless of whether they are considered part of a target demographic. That lack of optimisation becomes their strength.

Digital platforms increasingly shape cultural consumption through predictive systems that filter content according to user behaviour. Posters operate in opposition to this logic. They introduce friction. They interrupt routines and invite accidental discovery outside curated online environments.

Because public images reflect competing social values, encountering them in shared space can also challenge individual preferences and biases.8 Posters may expose viewers to events, communities or political viewpoints they would never encounter within personalised digital feeds. In this sense, the street functions as a counter-algorithm — one based on chance, proximity and coexistence rather than behavioural prediction.

Design Under Pressure

Melbourne’s poster culture also influences visual design itself. I would argue that the city’s abundance of visuals actively elevates design quality. When hundreds of posters coexist on the same surfaces, each one must actively compete for attention. This competition often results in bold typography, experimental layouts an highly distinctive visual identities.

These posters are designed to survive layered environments, weather conditions and visual overload. They must communicate quickly while remaining memorable. Compared to more regulated poster environments — where reduced competition can lead to safer and more standardised design — Melbourne’s visual density encourages stronger and more expressive communication.

Posters here are not nostalgic artefacts from a pre-digital era. They operate as contemporary communication tools, evolving alongside digital media rather than being replaced by it.

When Walls Speak

Melbourne does not simply allow posters to exist — it reveals what happens when public space remains visually negotiable.

Although flyposting operates in legal grey zones, its persistence demonstrates that public imagery is not solely shaped by policy or commercial branding. It is also shaped by individuals who choose to participate in the visual construction of their city.

Cities that prioritise visual uniformity often achieve clarity and order. Melbourne suggests an alternative model, where layered imagery reflects cultural diversity, public dialogue and grassroots participation.

Claims that print is obsolete overlook how media evolve rather than disappear. In Melbourne, print has not been replaced by digital communication; it operates alongside it as a shared, public and unpredictable form of cultural exchange.

Paper and paste add texture, colour and human presence to the urban environment. Posters make the city readable. They reveal what is happening, what communities care about, who is organising and who is speaking.

Melbourne feels alive because its walls remain open to being rewritten — one sheet of paper at a time.

︎︎︎

1 Meggs, Philip B, Alston W. Purvis, Meggs’ History of Graphic Design, New Jersey (John Wiley & Sons, Inc.) 2016.

2 Gemeente Amsterdam, ‘Mag ik posters plakken?’, <https://www.amsterdam.nl/leefomgeving/mag-posters-plakken/> [10.02.2026].

3 Biesenbeek, René, ‘Slechts één gemeente biedt voldoende openbare plakplaatsen’, in: Agora, April 1997, p.17.

4 Gemeente Papendrecht, ‘Richtlijnen Buitenreclame’, <https://lokaleregelgeving.overheid.nl/CVDR434984> [10.02.2026].

5 City of Melbourne, ‘Street art’, <https://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/street-art> [10.02.2026].

6 Andron, S, Chris Parkinson, ‘Power, Paper, and Profit: Street Posters and the Making of Visual Culture’, Space and Culture, 29 (2025) 1, pp.4-22.

7 Grassroots culture refers to cultural initiatives that originate from local communities, collectives or individuals rather than institutions, governments or large commercial organisations.

8 The Conversation, Sabina Andron, ‘Images shape cities — but who decides which ones survive?’, January 29, 2024, <https://theconversation.com/images-shape-cities-but-who-decides-which-ones-survive-its-a-matter-of-visual-justice-216003> [10.02.2026].